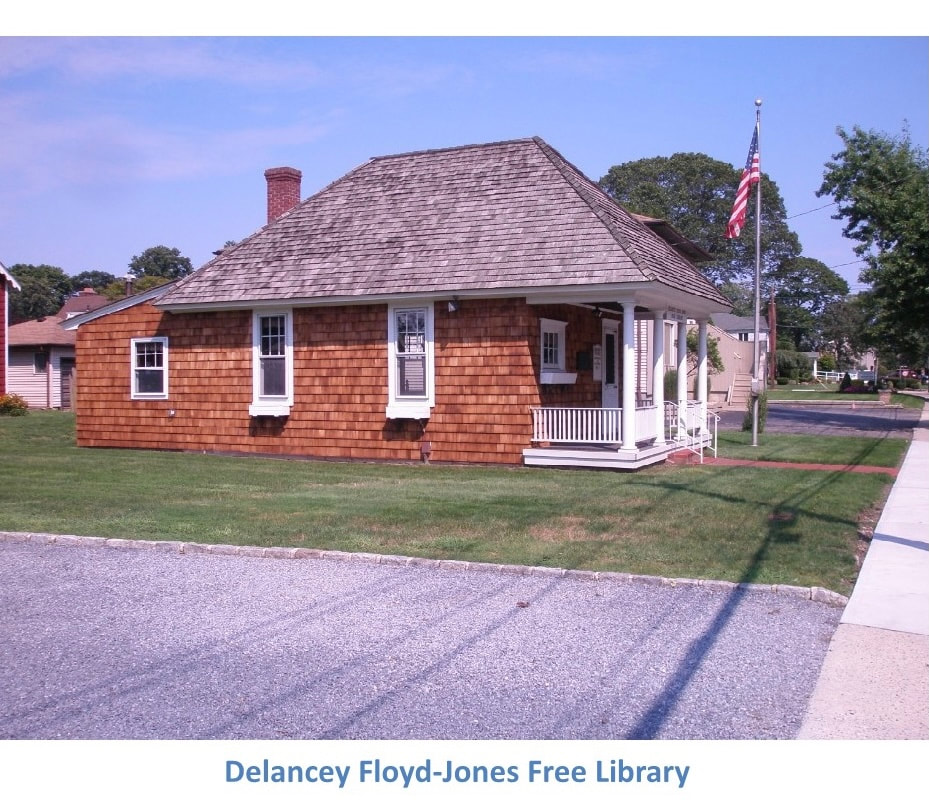

The Delancey Floyd-Jones Library opened in November 1896, so 2021 is its 125th year of operation. The library has served the Massapequas continuously since its opening and has undergone a significant transformation in response to the overwhelming changes in the area after World War II. Here are some dates and events that provide insight into its history. 1896 – Colonel Delancey Floyd-Jones, a career army officer, talked with Coleman Williams, husband of his cousin Sarah Floyd-Jones, about donating a small parcel of land east of Grace Church so a public library could be built. He paid Williams $60 for the plot and contracted with a carpenter to build a wooden building facing Merrick Road for $530.10. Relatives provided tables, bookshelves, fireplace implements, and $230.90 to purchase books. Most of the original furniture is still in the library. 1907 – Electricity was installed in the building, replacing candles that were used originally. A janitor was employed to maintain the building, which had no water, for $4 per month. A resident could purchase a key for $10 annually that allowed access to the library at any time. The library contains one of the original keys. 1932 – Edward Floyd-Jones left the library $2,500 in his will. The library was a separate corporation and money provided by several other relatives over the years was invested. 1952 – Trustees of the rapidly expanding public school system created a Floyd-Jones Library Committee to investigate how the building could best serve the community. Among the proposals were

Central to these discussions were two important considerations. The first was the legal issue of whether there could be two separate libraries. The New York Secretary of State ruled there could not be, because the state could not pay annual subsidies for two libraries in one school district. The other issue was the library’s endowment. After many meetings and much discussion, the Floyd-Jones Library Trustees decided to keep the library open and retain control of its endowment. 1969 – Students continued to come to the library, as evidenced by a file of cards signed by their parents, pledging to return books that were loaned or face fines. Fewer residents were using the building, however, so a Friends of the Library group was formed, in an attempt to attract more community participation. Members paid one dollar annually and could attend quarterly meetings. The Friends held bake sales, raffles and other fund-raisers. The group lasted about fifteen years, and had as many as 300 members, but petered out by the mid 1980s. 1984 – The Historical Society of the Massapequas was interested in moving an 1870 servants’ cottage, located behind the Bar Harbour Library, close to Old Grace Church. It was vacant and deteriorating rapidly. After several discussions, the Library Trustees agreed to lease a portion of their property north of the building and the Society moved the cottage across Merrick Road in July 1986. 1986 – Mrs. Paul Floyd-Jones Bonner, the last Floyd-Jones family member involved directly with the library, had resigned as Chairperson and a replacement could not be found. Fortunately, Eugene Bryson, a Trustee as well as a Vestryman in Grace Church, agreed to become the Chairperson and set out repurposing the library. He first had the rear storage room demolished and rebuilt to look like the rest of the library. He also applied for historic designation, eventually earning Town of Oyster Bay recognition. He retained the services of a professional librarian, to review the holdings and dispose of any duplicates or books no longer considered useful. Finally, he led the trustees to designate the library as a historic building. 2021 - The Floyd-Jones Library, rendered obsolete by the public library system, remains today as an historic structure. It is staffed by volunteers and is open on Wednesdays and Saturdays from 10 until 1. Please feel free to visit and experience an important part of Massapequa’s history.

2 Comments

3/22/2020 3 Comments A Brief History of the MassapequasThe area labelled Massapequa today was occupied for several thousand years by Native American tribes and didn’t have its first European settler until 1696, rather late in the settlement period. In that year, Thomas Jones, former soldier in King James II’s army and former privateer, was given 6,000 acres of land by his father-in-law Thomas Townsend, and moved here from Oyster Bay with his wife Freelove. He built a brick house somewhere south of Massapequa Lake and lived there until his death in 1713. He was, at various times, Ranger General, Sheriff, Tax Collector, Major in the Queens County Militia, and Chief Warden of the Episcopal Church, and operated a whaling station at today’s Jones Beach. He had seven children, some of whom remained in the area and built homes along today’s Merrick Road.

The first large Jones estate was Tryon Hall, built in 1770 by Thomas’s son David. It was occupied briefly by his son, also Thomas, a Tory Judge who was arrested three times during the American Revolution and forced to leave the New York colony and seek sanctuary in England. His niece Arabella and her husband Richard Floyd inherited the building and its property by agreeing to change their last name to Floyd-Jones. Most of the Joneses moved up to Cold Spring Harbor and became wealthy and influential business people there. The Floyd-Joneses stayed in the Massapequas and built many large estates along Merrick Road, such as Massapequa Manor, east of Massapequa Lake, Holland House, where St. Rose of Lima stands today, and Sewan, the site of Massapequa High School. They became the controlling family in the Massapequas until well into the twentieth century. Elbert Floyd-Jones, eager to have a convenient place of worship for his fellow Episcopalian family members, oversaw construction of Grace Church in 1844. It became the center of family worship for many years and gradually attracted other wealthy landowners, such as Cornelius Van De Water and James Meinell. The area also attracted other settlers after the American Civil War: Germans who settled in today’s Massapequa Park and farmers who bought or rented small plots of land in northwest Massapequa on either side of Hicksville Road. The area also attracted vacationers from New York City, who were drawn by its rustic charm and could reach it easily after construction of the South Side Railway in 1867. They came to hike, fish, hunt and later to swim in South Oyster Bay. The area was eventually home to fifteen hotels, including the Massapequa Hotel (1880 – 1914), known for its elegance and its proximity to Billy’s Beach, where Ocean Avenue runs to the Bay. Significant change to the area’s rustic character was threatened by Queens Land and Title Company’s attempt to create a city of 20,000 residents before World War I, located west of the Massapequa Preserve and north of Broadway. The area was also altered by efforts of the Brady, Cryan and Colleran real estate firm, who attempted to fill the area that is today Massapequa Park with private houses. Both efforts were unsuccessful through a combination of shady business practices and the depression of the 1930s. Enormous change had to wait for the end of World War II, when the Massapequas became what they are today, a community of private homes served by two major roads, a railroad and several business centers. The population of the Massapequas (the area that includes Massapequa, North Massapequa, East Massapequa and Massapequa Park) was about 3,000 in 1945. That number exploded to over 40,000 by the end of the twentieth century. Pent-up demand for private houses, coming from World War II veterans and New York City dwellers, led to the destruction of the mansions owned by Floyd-Jones family members and their replacement by private houses in developments such as Harbor Green, Biltmore Estates and Nassau Shores. German hotels and restaurants along Front Street were replaced by the Village of Massapequa Park, created in 1931. The farms in northwest Massapequa also disappeared, replaced by houses built throughout the area’s winding and irregular roads. The influx of residents forced the construction of schools, churches, libraries, movie theaters, parks, post offices, firehouses, restaurants, stores and later shopping centers, obliterating almost all vacant land in the Massapequas. The area we know today bears little resemblance to what was here until 1945, but stands as a vibrant and proud example of the suburbanization of the United States, the most obvious feature of our recent social history. 9/13/2019 1 Comment What Happened to the Joneses? The first child of Freelove and Thomas Jones was Sarah, born in 1695 and died in 1696. At the end of her short life (so common in the 1600s), she was buried in the Clifton Cemetery in Newport, Rhode Island. Her burial site is noted in Newport cemetery records, but there is no headstone, and may never have been one, given her short life. She was, nevertheless, the first Jones family member born on American soil.

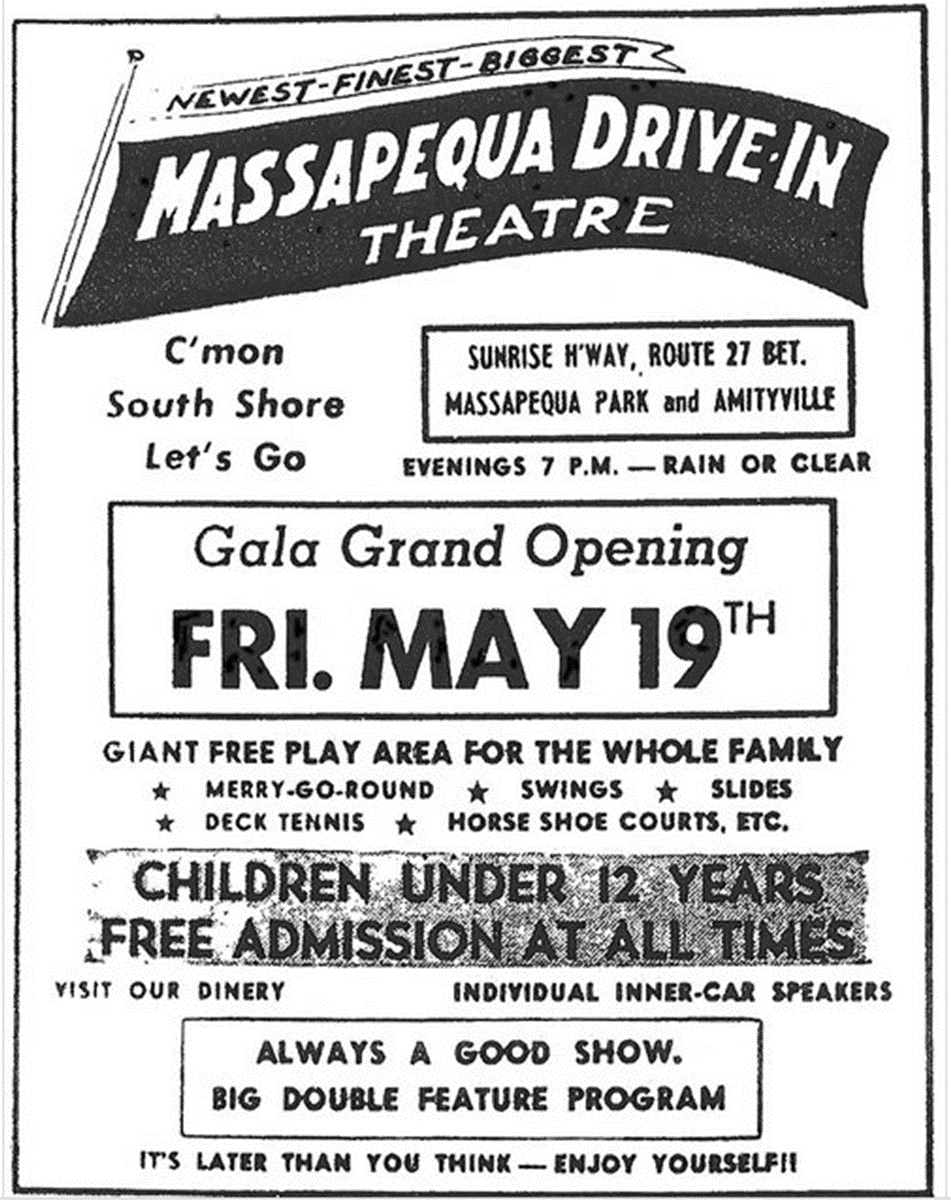

The last direct descendant of Freelove and Thomas was Mary Gardiner Jones, born in 1920 in New York City, where her father, Charles, worked as a lawyer. She grew up in Cold Spring Harbor and became uncomfortable with her family’s elevated social status and what she characterized as their constant fights over property in the Cold Spring Harbor area. Mary graduated from Wellesley College and worked for the Office of Strategic Services (later the CIA) during World War II. After the war she earned her degree from Yale Law School, graduating in the top 10% of her class. Despite her achievement, she interviewed with fifty law firms, several of whom explicitly said they would not hire a female attorney, before she found a staff position at the firm of Donovan Leisure in Washington, D. C., becoming the firm’s first female lawyer. Her way was eased by William (Wild Bill) Donovan, the head of the firm, who had founded the OSS and knew Mary Jones from her work there. In 1953 she took a position with the Justice Department, working in its anti-trust division. She eventually attracted the attention of the Kennedy administration because of her consistently strong positions against unrestrained business activities. In 1964 President Lyndon Johnson appointed her as the first female Federal Trade Commissioner. Her appointment came at an appropriate time, as the public was beginning to focus on consumer issues and had become receptive to the idea of government challenges to previously common pro-business practices. The climate was ripe for her to move the Federal Trade Commission in a different direction. Mary Jones refocused its efforts on consumer education and protection. She succeeded in having all cigarette advertising banned from radio and television. Later on she enacted rules that required garment manufacturers to add care labels to their products. She also brought lawsuits against real estate groups that engaged in redlining, the then common practice of segregating neighborhoods so that they were unavailable to prospective black homebuyers. Throughout her tenure, she supported regulations that won praise from consumer advocacy groups. After leaving the FTC, she taught law at the University of Illinois, founded the Consumer Interest Research Institute, and later established the D. C. Mental Health Organization, to assist children and senior citizens with mental health problems. She also published, in 2007, her very interesting autobiography Tearing Down Walls: A Woman’s Triumph. Mary Gardiner Jones never married, and upon her death in 2009 became the last of Thomas Jones’s direct descendants. She is buried in the Memorial Cemetery of St. John’s Church in Laurel Hollow. Interestingly, she is buried in the family plot of her mother Anna Livingston Short Jones, rather than in the very large Jones plot in the same cemetery. Perhaps in death she wanted to underscore one final time her discomfort with her family’s status. 5/11/2018 2 Comments Freelove Townsend Jones Freelove Townsend Jones was the wife of Thomas Jones, and together they were the first European settlers of the Massapequas. Much has been written about Thomas, but Freelove deserves to be highlighted because Thomas would not have received his unique wedding present if he had not married her. The Townsend family was not the first European family in Oyster Bay, which included all lands from Long Island Sound to the Atlantic Ocean, in what is today eastern Nassau County. The northern part was settled in 1653 by British subjects, following the purchase of most of the land that became the township of Oyster Bay from the Sachem Assiapum. Three Townsend brothers, John, Henry and Richard settled in Oyster Bay in 1661, having moved from Flushing and Jamaica after disagreements with Dutch governors. They may have become Quakers and supported other Quaker settlers. Both the Dutch and later the British hated the recently-formed Quakers because of their scorn for Protestant beliefs and practices. The Townsend brothers doubtless felt more welcome in Oyster Bay because of the presence of other Quakers and the more relaxed attitudes of the British settlers residing there. John Townsend had several sons, among them Thomas, who had advised his mother Elizabeth to draw up a will to provide for her younger children after John’s death in 1668. The children received property in or near Oyster Bay, while Thomas received money and influence as the holder of several titles: Captain of the Militia, Constable, Surveyor, Recorder and Justice, significant posts in a town that was growing in all directions. Thomas bought a large tract on the southern part of Oyster Bay from Sachem Tackapausha in 1679 and held it for several years. In 1692, he met Thomas Jones in Rhode Island. They became friendly and Jones moved to Oyster Bay in 1695, perhaps to distance himself from his reputation as a pirate or a privateer. In 1695 Thomas Jones married Thomas Townsend’s eldest daughter Freelove, who was born in 1674. Thomas had wanted his oldest son John to take the southern portion of his land, but he declined, asking “Does my father want me to go out of the world?” Oyster Bay had dozens of houses by this time, on well laid out streets with easy access to Long Island Sound. While there were settlers in neighboring Seaford (from 1643) and Amityville (from 1658), the Massapequas were unsettled. Even the few Native Americans who had lived there were moving away by the late 1600s, aware that they no longer had free access to their land and that they would be replaced by white settlers, by force and bloodshed if necessary, as was happening throughout Long Island. In this context, Townsend offered the land “out of the world” to Thomas Jones, who was not employed in any easily identifiable occupation at that time. Jones was already the recipient of a house Thomas Townsend had built in Oyster Bay, and Freelove and he settled there after their marriage. There is also a map of the “Town Spot” of Oyster Bay, drawn up around 1700, that shows Freelove’s name on two parcels of land on South Street. In addition to these properties, then, Thomas Jones would become the owner of most of the southern portion of Oyster Bay. Jones accepted this generous wedding gift, moving south to what was then called Fort Neck and building a brick house on the west side of the Massapequa River, near today’s Merrick Road (then called Kings Highway). Freelove and he settled there and had eight children, six of whom survived to adulthood. We don’t have much information about the way they lived and how difficult it may have been for Freelove, other than the common condition that childbirth was very traumatic, with many children and their mothers dying from the experience. It seems likely that Freelove traveled to Oyster Bay when ready to give birth, because of her extensive family and access to midwives and other helpers. It’s notable that her first child Sarah died in 1696 and was buried in the Clifton Burial Ground in Newport, Rhode Island. The likely connection is that her father Thomas was at that time living in Rhode Island as Newport’s Sheriff. Thomas Jones prospered in South Oyster Bay, taking on a remarkable number of responsibilities as granted by the English Governor. He also was allowed to conduct whaling operations along the entire south shore, according to a 1710 license granted by Governor Hunter. He and Freelove obviously lived well and were accepted as full members of the community. Freelove, in fact, converted in 1702 from Quakerism to the Episcopal religion, practiced by most English settlers living in Queens County at that time. She remained committed to her new faith and raised her children as practicing Episcopalians. We know that Freelove and Thomas traveled regularly between their home at Fort Neck and Oyster Bay, and very likely to Newport to visit her father. In one instance, Freelove expressed her thirst as they were traveling from Fort Neck to Cold Spring. Thomas identified a spring with fresh water and collected some from his hat, providing water for Freelove, as well as some for himself and his horse! Freelove and Thomas made several land purchases in the early 1700s in Oyster Bay hamlet. Thomas Jones died in December 1713, leaving the lion’s share of his property to his wife. She divided her time between Oyster Bay and Fort Neck raising her six children, none of whom were adults. Her oldest, David, was fourteen and her youngest, Elizabeth, was three at the time of their father’s death. In 1715 she married Major Timothy Bagley, an Irishman sent with other British soldiers to defend the colonies against the French. He subsequently became Ranger General and took over Thomas Jones’s whaling operations, securing a license to make oil from captured whales “driven on shore on the south coast of Long Island Sound” (John Henry Jones, The Jones Family of Long Island). Freelove continued to live well and saw most of her children grow to adulthood. She died in 1726, by which date her youngest daughter, Elizabeth, was sixteen. Thomas had died at 48, Freelove at 52, common life spans in the early 1700s and for people living in a challenging and difficult frontier environment. She was buried next to Thomas, first behind their brick house above Massapequa River (then called Brick House Creek), and later reinterred in 1892 in her current resting place in the Floyd-Jones Cemetery behind Old Grace Church. Her tombstone reads: Here Lyes Interd The Body of Freelove Bagley Daughter of Captn. Thomas Townsend of Rhode Island First Married to Maj Thomas Jones After His Death To Major Timothy Bagley She Died July 1726 2/10/2018 7 Comments Going to the Movies Interior Shot of the Pequa Theatre Interior Shot of the Pequa Theatre As the Massapequas became heavily populated in the years after World War II, stores, churches, schools and entertainment centers developed to meet the needs of new homeowners. It’s revealing to notice that for many years any resident wishing to go to indoor movies would need to travel outside Massapequa (as they need to do today)! The Massapequa Post in 1955 advertised movies showing in Amityville, Merrick and Farmingdale, but none in the Massapequas. The first indoor theater was created in September 1960 on the second floor of the newly-opened Bar Harbour Shopping Center (today Southgate Shopping Center). The first feature was “The Mouse That Roared,” shown on a wide screen with air conditioning. That theater lasted until 1980, when the Southgate Apartments were built and the shopping center was redesigned with fewer stores. The theater was subdivided into several businesses, which continue to occupy the space today. The Pequa Theater opened about the same time and was designed as a modern, high-ceilinged theater on Sunrise Highway (see image). It featured an all-glass lobby and exposed ceiling joists and showed adult themed first run movies. Long-time residents remember that it was a very comfortable theater with good sight lines and acoustics. It closed later than the Bar Harbour Theater, lasting until 1988, when it was purchased by a car dealership. The Datsun Motor Company (later changed to Nissan) bought the site and it is today a Nissan and Infiniti dealership. One of the most unique theaters built in the entire Long Island area was the Jerry Lewis Theater, opened in December 1972, on the site of a former drive-in. Love At First Bite was the first showing. Jerry Lewis was an enormously popular entertainer, in the 1950s with his partner Dean Martin, in the 1960s as a star in many comedy films, and from the 1970s as director of the Labor Day weekend telethon to raise money for Muscular Dystrophy research and treatment. He combined with the Network Cinema Corporation to open a chain of theaters across the country. These would be small, with about 200 seats, technologically sophisticated so they could be run by as few as two people, showing second run family run movies and charging low admission prices to attract families. Three others were located on Long Island, in East Meadow, Lake Ronkonkoma and Center Moriches. There was, however, little advertising or oversight of each theater, so it was left to the franchisee to sink or swim. Most sank very quickly, including Massapequa’s theater, which closed in 1980. The building subsequently housed several businesses and is today a Staples store in the rear of the Phillips Shopping Center. Of the 130 theaters in the Jerry Lewis chain, 12 are still open, under different names. There are none in the New York area. The Jerry Lewis Theater replaced the first theater in the Massapequas, the Massapequa Drive-In, which opened in 1952 to the rear of what was Frank Buck’s Zoo and became the much smaller Grimaldi’s Kiddie World. The theater was one of many drive-ins that opened after the war across the country. Several others on Long Island included those in Valley Stream, Bay Shore, Westbury and Huntington. They were very popular with families and with teenagers (for reasons that won’t be discussed here).The Massapequa Drive-In showed double features, such as From Here to Eternity and The Solid Gold Cadillac in June 1960. It was usually opened in the warmer months, but there are advertisements in the Massapequa Post about shows in the winter (Quo Vadis in January 1965, for example). The Massapequa site felt the same pressure as other drive – in locations as the population grew and demands for houses and stores increased. It lasted until 1972, when it was replaced by the Jerry Lewis Theater and several other stores in the Phillips Shopping Center. All theaters listed above were small, most with one screen, but the 1970s saw the growth of cinemas with many screens, typically five to ten, offering a wide variety of choices. One of these was the Multiplex at Sunrise Mall. The Mall opened in 1973 and the theater in 1976, operated by United Artists. There were originally five screens. Two were added in 1979. Entry was originally on the first floor, but the box office was moved in the early 90s to the second floor, in the center of the mall. Although very popular in the beginning, the site suffered declining attendance through a combination of vandalism and the development of the Farmingdale Tenplex, a few miles north on Route 110. The theaters closed at the end of their lease in 1999 and are now the sites of several stores. Last and possibly least, there was a small theater in North Massapequa, housed in the shopping center located today at the northwest corner of Jerusalem Avenue and Hicksville Road. It opened in October 1960 and closed in the late 1970s. It was located on the first floor of a two-story building, with a Fred Astaire Dance Studio on the second floor. Patrons remembered being distracted by the dancing, especially the tap classes. Little else is known about the theater except that the Marshall’s Store now occupies the site. Anybody who remembers its name or other features is welcome to comment on the website. |

AuthorGeorge Kirchmann Archives

July 2021

Categories |

Search by typing & pressing enter

RSS Feed

RSS Feed